Three cheers for CVS, science denial gets crazy, diabetics missing out, and more

16 Feb 2022

Posted by Andrew Kantor

The good drugs diabetics aren’t using

Patients with type 2 diabetes can benefit from two kinds of drugs — glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.

(If you made it through that first paragraph, I thank you.)

Oddly, though, those meds aren’t being prescribed or used very often.

In fact, from 2018 to 2020, only 11 to 14 percent of adults with type 2 diabetes received either one (according to Yale researchers). In fact, not only were there few new prescriptions, but those that were written often went unfilled.

[A]mong patients who started these medications, only two-thirds were consistently taking these medications at 3 months and only half one year after starting the treatment.

So what’s the deal? These are U.S. patients, so the issue appears to be money — the average out-of-pocket cost was $1,000 to $2,000 per year, and continued use was higher among higher-income patients.

ICYMI

Robert Califf was confirmed as FDA commissioner. That is all.

Kids aren’t getting long Covid

Yesterday we told you that long Covid — particularly cardiac issues — affects even people with a mild case of Covid-19.

But here’s good news: There had been a lot of concern of kids, even with mild cases, ending up with long Covid to some degree. That fear came from some initial reports, which were mostly anecdotal.

Now we’re getting real data from real studies, and it means parents can breathe a small sigh of relief. Yes, a small percentage of kids do have symptoms that last but …

These studies indicate that long Covid in children is rare and, when it does occur, is short-lived. In one study, 97% of children ages 5 to 11 with Covid-19 recovered completely within four weeks […] most had fully recovered by eight weeks.

Side note: If you were hoping for some depressing news today, here: The effect of a Covid vaccine booster appears to start waning after four months. Happy?

The least they could do

CVS is now ensuring its pharmacy staff gets a lunch break.

HIV cured again

Another patient — a woman in New York — has been cured of HIV … probably. She’s only the fourth person in the world cured of the disease. (Two others somehow fought off the virus without specialized treatment.)

This treatment involved using a combination of umbilical cord blood (from an infant donor) and adult stem cells in a procedure known as a haplo-cord transplant, originally designed for cancer treatment. At the moment it’s only suitable for about 50 patients a year in the U.S., but the fact that it works continues the push toward a common cure.

Utter disbelief

The latest survey from the Covid States Project* found some disturbing numbers: Not only do a notable fraction of Americans believe incorrect information about Covid-19 and its treatment, but a substantial number believe that information while acknowledging that actual scientists don’t.

As of January 2022, about 5% of our respondents thought that vaccines contained microchips, 7% said that vaccines used aborted fetal cells, 8% believed vaccines could alter human DNA, and 10% were concerned that vaccines could cause infertility.

Those are people who are flat-out wrong. But almost half the people surveyed (46 percent) “reported being uncertain whether at least one of those claims was true or not.” Oh, and that includes one in five Americans who said that even though scientists say a particular vaccine claim is false, they’re unsure about whether to believe it.

Here’s a fun fact, though:

Among those who claimed to have expert knowledge, 48% believed false claims compared to only 16% of those who said they knew almost nothing about vaccines.

Read the full survey report here (PDF).

* A joint project of Harvard Medical School and Northeastern, Harvard, Rutgers, and Northwestern universities

States of confusion

But it’s not just random people on the street. Even some state legislatures are fighting back against facts and science.

As state medical boards (led by the national Federation of State Medical Boards) attempt to crack down on physicians who spread misinformation about Covid-19, those legislatures are trying to stop the boards — i.e., to allow healthcare workers to give patients incorrect or unproven information.

Georgia is not among these states; the Composite Medical Board has, in fact, put out a statement, “Physicians who generate and spread COVID-19 vaccine misinformation or disinformation are risking disciplinary action by state medical boards, including the suspension or revocation of their medical license.”

In Tennessee, though, it’s gone so far off the rails that the legislature threatened to disband the Board of Medical Examiners after it unanimously voted to consider license suspension for doctors spreading COVID-19 misinformation, including — I kid you not — physicians who say that vaccines could contain microchips.

“If you’re spreading this willful misinformation, for me it’s going to be really hard to do anything other than put you on probation or take your license for a year. There has to be a message sent for this. It’s not OK.”

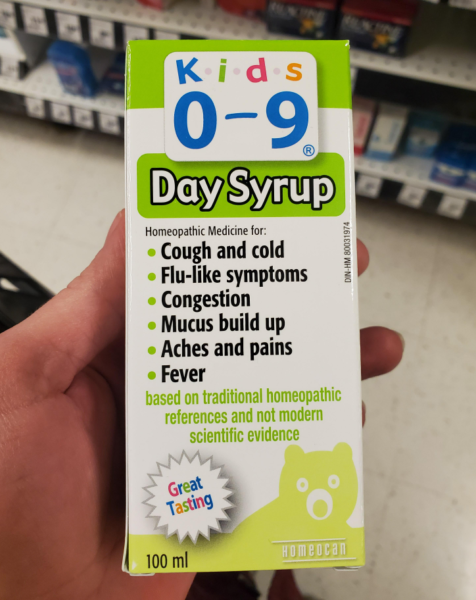

When the anti-science is a selling point, you know we’re in trouble.

Hormones to the rescue

Post-menopausal women who contract Covid-19 have an extra treatment at their disposal: estrogen. So found Swedish researchers (and one token Finn) after scrutinizing 14,685 women’s health records.

Whether for endocrine therapy or receiving hormone replacement therapy, women taking estrogen supplements were less likely to die from Covid. As usual, ‘Further trials are needed.’

Your brain says “Put the cookie down”

There is a specific region of the brain that’s responsible for feeling full after eating. (But you didn’t know that because it was just discovered.)

University of Arizona neuroscientists thought that the central amygdala was involved, but that’s like saying “John lives in Canada.” It needs to be narrowed down. Which they did. It turns out that the effect is controlled ‘downstream’ of the central amygdala by the parasubthalamic nucleus (PSTh).

Well, at least controlled enough for that to be a potential target for new therapeutics.

“[W]e hope to identify the neural mechanisms that control eating and control emotion and how they interact with each other. This knowledge can help us develop a more specific treatments.”