$3.00 flu prevention, giving insurers a taste of their own medicine, improving GLP-1s, and more

13 Jul 2024

Posted by Andrew Kantor

Easy infection prevention

A couple of simple, over-the-counter products can prevent colds, chest infections, and even the flu from taking hold.

We won’t bury the lede. The products are Vicks First Defence* gel-based nasal spray or — get this — a simple saline nasal spray. According to British researchers…

[B]oth sprays were shown to reduce the overall illness duration participants experienced by around 20 per cent, and resulted in a 20-30 per cent reduction in the days lost of work or normal activity.

That’s based on a study of 13,800 adults who either got one of the two sprays, or “an online resource promoting physical activity and stress management.”

Tidbits:

- Most of the patients didn’t use the sprays as often as they were asked to, but they still worked well.

- Even that online resource helped a bit, reducing infections by about 5 percent.

* Bad news: As you might guess from the misspelling, Vicks First Defence is a British product, but we did find it on Amazon in the US as “Vicks Prèmiere Défense” — at $28 a bottle.

Sauce for the (insurance) gander

Insurers: We’re using AI to automatically deny treatment claims and prior authorizations.

Doctors: Fine. We’ve got AI too, and we’re going to use it to draft requests and appeals with a heck of a lot of detail.

With the help of ChatGPT, [one doctor] now types in a couple of sentences describing the purpose of the letter and the types of scientific studies he wants referenced, and a draft is produced in seconds.

Then he can tell the chatbot to make it four times longer. “If you’re going to put all kinds of barriers up for my patients, then when I fire back, I’m going to make it very time consuming,” he said.

They’re actually using a product called Doximity GPT (based on ChatGPT), which is HIPAA-compliant. It uses not only scientific studies to make its case, but also patient medical records and the insurer’s coverage requirements. And it works.

GLP-1 v2?

Side effects are a big downside to GLP-1 agonists, and nausea is a big one. It’s kind of a “you take the good, you take the bad” situation.

But researchers at Philly’s Monell Center found something interesting. It seems that GLP-1 inhibitors affect two types of neurons. Some neurons affect satiety, i.e., feeling full, while some affect nausea. (Want more Latin? The GLP-receptive neurons that affect satiety tend to be in the hindbrain’s nucleus tractus solitarius, while the ones that are more “aversive” are in the area postrema.)

All this means, the Monellites figure, that it might be possible to target just one set of neurons, so people felt full without the side effect of nausea.

This is all in the early stages, but they’re really into the idea of “separating therapeutic and side effects at the level of neural circuits.”

Natural killers: the sequel

CAR-T cancer treatment works by taking a patient’s own T cells, modifying them to attack cancer, and reintroducing them to do their killing. But there are serious side effects — including death.

Enter CAR-NK therapy, which uses natural killer cells instead of T cells. Those don’t need to be taken from the patient’s own body (making them easier to get) and they don’t have CAR-T’s side effects. The downside is that while they work well against leukemia, they can’t work against solid tumors like breast cancer.

Yale researchers, though, might have a way around that. They were able to disable some of the CAR-NK cells’ “brakes” — the cellular-checkpoint genes that keep them from becoming too active, notably a gene called CALHM2 that, when knocked out, “made natural killer cells more potent in terms of cancer-killing, more efficient in terms of infiltrating the tumor, and more efficient in producing anti-tumor cytokines.”

Now they’re looking at the details of why this works, with a plan to develop a treatment for clinical trial.

Elsewhere: Penn’s PDMP

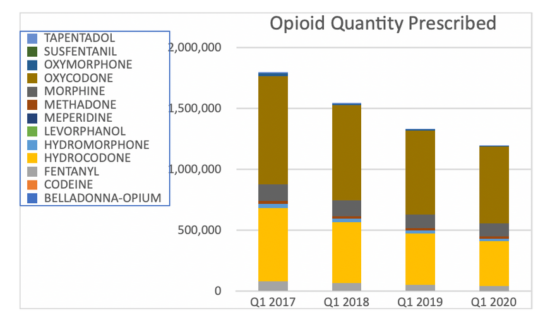

How well do prescription drug monitoring programs work? In Pennsylvania at least, really, really well.

Researchers there looked at a simple metric: opioid prescription rates. They found that prescriptions for opioids dropped 38% from 2017 to 2020; the PDMP took effect January 1, 2017.

Side note: The biggest percentage drops were in meperidine (Demerol; down 89%) and fentanyl (down 51%).

The big limitation/missed opportunity is that they didn’t look at records before the PDMP was required, to see if opioid prescribing was already decreasing.

Phage breakthrough

Here at Buzz we’re big fans of bacteriophages and their potential to treat infections when antibiotics fail. Phages have a few problems, though. They have to be matched to specific bacteria, for one. And to be transported they need to be suspended in liquid and refrigerated or frozen, so labs around the world don’t share as much as they could.

Now Canadian researchers have developed a way to help solve those problems — they can store the phages at room temperature in trays that also serve as a testing medium to match phages to bacteria.

That means, in principle, that a hospital looking to fight an infection could receive a tray of candidate phages and know within an hour or two if any of them could fight the bacteria they’re facing. It also means they could save those phages in their own library for the future.

“If everything moves forward to commercial application as we anticipate, this could revolutionize the way we use phages for different purposes.”