Health workers shun vaccines, Flu Index launches for ’24, how Canada deals with shortages, and more

05 Nov 2024

Posted by Andrew Kantor

The Flu Index is back

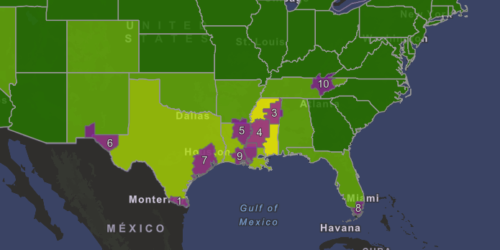

Walgreens’s annual Flu Index is back for the 2024–25 season, and so far it’s showing low activity in most of the country. Mississippi is in the worst shape; it’s in the middle of the index at yellow, while Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Texas are all slightly above “low.” Georgia is ranked #10 of all states, but we’re surrounded by the sick, so that might not last.

Canadian resiliency

Even after drug supply chains were disrupted, Canadians saw fewer shortages than we did down here in the States. That’s what a joint study from the universities of Toronto and Pittsburgh found after looking at supply chain issues in both countries between 2017 and 2021.

The countries have similar regulatory structures, and the researchers only considered the effect of similar shortages. They found that supply chain issues caused a shortage in the US about 49% of the time, but the same issues only caused a Canadian shortage 34% of the time.

So what’s the difference?

The biggest factor, they found, is that Health Canada has better relationships not only with drug makers, but with other stakeholders such as wholesalers. That gives the Canadians more information about impending shortages, and the government the ability to react more quickly. (In the US, for example, manufacturers don’t have to give a reason for their shortages, which the researchers called “suboptimal” as it doesn’t provide useful information to health authorities.)

Also, while the US has an emergency national stockpile for “acute events,” Canada’s stockpile is available to alleviate shortages caused by supply chain issues. The result:

Although both countries were affected by drug-related supply chain issues during this period, reports were 40% less likely to result in meaningful drug shortages in Canada.

TB takes the #1 spot

Tuberculosis has taken Covid-19’s place as the world’s number one infectious disease. In 2023, according to the WHO, 8.2 million people were newly diagnosed with TB around the world — the highest total ever recorded, and a 9% increase from the previous year.

The good(ish) news is that, while infections were up, TB deaths were down in 2023 to about 1.25 million. In contrast, Covid-19 ‘only’ killed about 320,000 people that year.

Microscopic targeted tumor killer

MIT researchers have found a way to deliver a double-whammy of therapy to fast-growing tumors, which they say was more effective and has fewer side effects than current chemo options.

The one-two punch: a chemo drug and heat, both delivered via an implantable microparticle. Implantable in the tumor, that is. Once in place, an infrared laser is used on it. That both releases a drug encased in the particle and causes the particle to heat up. And tumors hate heat.

The result is on-demand, localized treatment — no broad chemo necessary. And it works; in early tests on mice, this dual therapy wiped out aggressive tumors and significantly improved survival rates compared to single treatments.

The X for Y files: a tau-tangle buster

The glaucoma drug methazolamide (a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor) reduced the buildup of the tau protein that’s a hallmark of dementia … in zebrafish. British researchers took advantage of the fishes’ short lifespan and quick breeding to test 1,437 drug compounds against “tauopathy” and found that methazolamide seemed to work. Then they tested it on mice, and discovered “that those treated with the drug performed better at memory tasks and showed improved cognitive performance compared with untreated mice.”

Next up: Testing methazolamide against other diseases such as Huntington’s and Parkinson’s, and possibly moving along to human trials.

What, them worry?

Workers in healthcare facilities are taking precautions against the flu, but Covid-19? Not so much. New CDC data found that 81% of personnel in acute care hospitals got this year’s flu vax, but only 15.3% of them got the updated Covid shot.

In nursing homes it was a lot worse: Only 45.4% of personnel there got flu shots, and only 10% of employees got the latest Covid shots.

In both cases, the South lagged the rest of the nation with notably lower vaccination rates, as did independent contractors (i.e., non-staff). Perhaps they figure their patients are more resilient to respiratory illness.

Treat the person, not the test

You’ve got an ICU patient with hospital-acquired pneumonia. You’ve got two choices when choosing an antibiotic: You can do tests for common pathogens to decide which drug will likely be more effective, or you can consider some patient-specific risk factors.

Researchers at the universities of Michigan and Kansas studied ICU patients, then they did a lot of fancy math to figure out which method (if either) was better.

The answer: Forget testing and go with a ‘risk factor–based regimen.’ Not only did that turn out to be more appropriate more often (89.9% vs 83.7%), it also cut down on the unnecessary use of combination therapy — something that occurred almost 70% of the time when a pathogen test was used.